In a small'ish port town a reformatory girl (and ex-gang member, Swedish style) (Nine Christine Jönsson) under the terms of her probation labors in a factory while boarding involuntarily with her mother. A flashback reveals her problems stem for the most part from the broken marriage of her parents, although what might come off as a rather simplistic formative trauma is kept to a minimum of exposition, a sketch, really, within the contemporary narrative proper. (During this scene, for the first time in Bergman a clock ticks on the soundtrack. A bell tolls minutes later after three of her inebriated co-workers challenge her date [Bengt Eklund], "the salty sea-dog," to a rumble.)

Mirror reflections, and double compositions, irony of the self, irony of comparison.

Much of what I'd written here was lost thanks to the Blogger window being open for a period of time beyond twelve hours, which knocks off the auto-save function, and I was too stupid to hit command-A command-C before closing the window. A run-through recap of what I might have written:

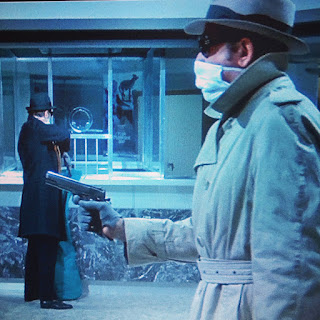

-There's the ex-gang-member friend in need of an abortion. She's accompanied by Berit (Jönsson) and Gösta (Eklund) to the procedure in a back room, but post-op all hell breaks loose, and in a portrayal, although not graphic, far beyond what most mainstream Western cinemas would agree to show in 2020, let alone 1948.

-Berit confides her history to Gösta in the way of men and the reformatory, who in turn shocks after the flashbacks of her actions by uttering, "How many guys have you HAD? ... Why couldn't you have kept your mouth shut?"

-The abortionist smears makeup on Gertrud directly post-procedure as though she's already a corpse. A shot and a pill, and she will abort in a week or so... except she dies straightaway...

-The police question Berit. "If you tell us the abortionist's address we can all go home." Negotiations, not to drag Berit through the mud in court. Her attitude matters a great deal to these bureaucrats, who threaten her with being an accomplice to murder.

Berit, post-probation, and Gösta contemplate running away on a departing ship. They don't. Something about hanging around and sticking it to the olds. In short, Port of Call [Hamnstad, 1948] sticks out liberal, provocative ideas in the way of youth living, sex, and consequences, but the film ends when it ends (this is not an original Bergman manuskript), and it's likely enough that the master, still in his relative apprenticeship, found it most advantageous to move on to the next project. •

Kris [Crisis, 1946]

Skepp till India Land [Ship to India, 1947]

Hamnstad [Port of Call, 1948]

Törst [Thirst, 1949]