Uncle on a Roadshow

The first thing that comes to mind when I think of Varda's Uncle Yanco [1967], besides Agnès's purple sweater-top, is the moment when Yanco tells his niece something like, "The hippies like me because I have long hair." This statement perfectly exemplifies 1967 because it's the last year where the long hair hasn't really even grown in yet. Uncle Yanco is a portrait of love, reentanglement of uncle and niece, that captures the last optimistic moment in time in the Bay Area: before things got uglier for those who weren't even chanced to get ensnared in Vietnam...

Jean ("Yanco" the Greek) Varda, splendid artist, occupies the space of and between a passeur of media, like Agnès herself in her film researches. For Yanco, is his medium architecture? (Henry Miller called him the last architect.) Is the primary medium painting/collage?

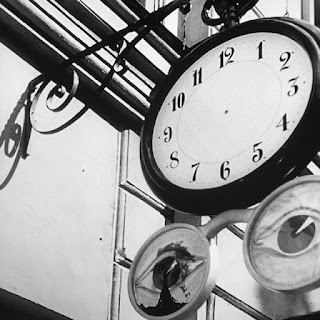

In her 2007 introduction to the film, Agnès notes that she had "heard of Yanco in San Francisco" (from the Miller book?) — so she went to visit him, a curious family tree-graft! She had three days to shoot the utopia of 1967 Sausalito's "aquatic suburbia," which commences when she decides, "We re-enact this avuncular moment," with her embrace with Yanco. The children hold aloft in frame the gelatin heart. Varda makes a three-step out of her entrance, as in previous films, namely Cléo de 5 à 7.

It's a question of art, but a question too of taste. This '67 annus mirabilis will soon push the critical question to the fore in its forcing one to consider popular (populist?) psychedelia against the entrenched norms, — entrenched as the traveler's loose teeth bulwarking an acid swish. •

Other writing on Agnès Varda at Cinemasparagus:

La Pointe-Courte [1955]

Ô saisons ô châteaux [O Seasons, O Châteaux, 1957]

L'Opéra-Mouffe, carnet de notes filmées rue Mouffetard par une femme enceinte en 1958 [The Opéra-Mouffe: Diary Filmed on the rue Mouffetard in Paris by a Pregnant Woman in 1958, 1958]

Du côté de la Côte [Around the Côte, 1958]

Les fiancés du pont Mac Donald, ou (Méfiez-vous des lunettes noires) [The Fiancés of the Pont Mac Donald, or: (Beware of Dark Glasses), 1961]

Cléo de 5 à 7 [Cléo from 5 to 7, 1962]

Elsa la Rose [Elsa the Rose, 1966]

Les créatures [The Creatures, 1966]

===