"Truffaut mode d'emploi" - Part One

(all translations by Craig Keller, from the French)

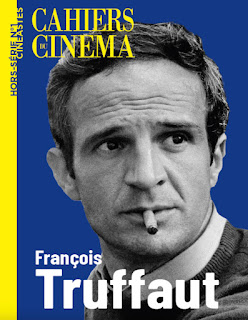

As of April 2023, Cahiers du cinéma have launched a new series of thick special issues (outside the regular subscription series) called "Cinéastes" ("Filmmakers"), editions of which will be released roughly twice a year, and which consist of a wide-ranging investigation of a director's biography and complete body of work. This inaugural issue, edited by Thierry Jousse and Marcos Uzal, is devoted to François Truffaut, and takes as its blueprint the essential special issue of the Cahiers known as Le roman de François Truffaut [The Novel of François Truffaut] published shortly after the director-critic's death by a brain tumor in 1984. Both editions supplement one another; the earlier might be a bit longer; the later work itself numbers 133 pages, and includes a few reprints from Le roman. All future numbers of "Cinéastes" will consist of a mixture of texts from Cahiers issues past, and articles newly commissioned for the series. In their editorial "Truffaut mode d'emploi" ["Truffaut User's Manual" or "A Guide to Truffaut"], Jousse and Uzal write: "For this first issue, the name of Truffaut sprang to mind very quickly. First off, because the filmmaker exercised, from the outset, his critical gifts in the Cahiers and because he was, by and far, linked to the history of this revue. But another thing, and maybe most especially, because his films continue to touch and to stimulate us, to this day, almost forty years after his too-early passing. Imperfect, varied, playful, and sometimes tragic, his œuvre has nothing of 'the monument' about it. On the contrary, when one revisits his films, one is almost always struck by their impurity, their inventiveness, and their paradoxical aspect." An accurate summation of the work of this master, who is not only among my favorite filmmakers in all cinema, but also probably my single favorite film critic, with Serge Daney (who appears in this issue) a close second. Without further ado, some translated excerpts from this landmark compilation. If you can read French (and even if you don't), I urge you to pick up a copy at Amazon.fr, FNAC, or the Cahiers online boutique itself; you can order it here.

===

Truffaut's List of the Ten Best American Talkies, Cahiers nº 150-151, December 1963

(in chronological order)

Scarface [Howard Hawks, 1932]

You Only Live Once [Fritz Lang, 1937]

The Magnificent Ambersons [Orson Welles, 1942]

Notorious [Alfred Hitchcock, 1946]

The Saga of Anatahan [Josef von Sternberg, 1953/1958]

Johnny Guitar [Nicholas Ray, 1954]

Rear Window [Alfred Hitchcock, 1954]

A King in New York [Charles Chaplin, 1957/1973]

North by Northwest [Alfred Hitchcock, 1959]

===

Truffaut's List of the Best French Films Since the Liberation, Cahiers nº 161-162, January 1965

(in chronological order)

Les enfants du paradis [The Children of Paradise / The Children of the Cheap-Seats] [Marcel Carné, 1945]

La Poison [Sacha Guitry, 1951]

Le carrosse d'or [The Golden Coach] [Jean Renoir, 1953]

Nuit et brouillard [Night and Fog] [Alain Resnais, 1955]

Lola Montès [Max Ophüls, 1955]

À bout de souffle [Breathless] [Jean-Luc Godard, 1960]

L'enclos [Enclosure] [Armand Gatti, 1961]

Le testament d'Orphée, ou Ne me demandez pas pourquoi [The Testament of Orpheus, or: Don't Ask Me Why] [Jean Cocteau, 1959]

Procès de Jeanne d'Arc [Trial of Jeanne of Arc] [Robert Bresson, 1962]

Les parapluies de Cherbourg [The Umbrellas of Cherbourg] [Jacques Demy, 1964]

===

from

Ali Baba and the "Politique des Auteurs"

On Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs [Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves] by Jacques Becker

by François Truffaut, 1955

Circumstances required that I see Ali Baba twice in a little theater with no ambiance before finally watching it again on a much more adequate screen, one night on Christmas Eve in the midst of five thousand spectators at the Gaumont-Palace among whom — as Renoir put it — only three people were able to "get it." Is it necessary to clarify that I lined up straightaway alongside those three select suspects, besides the existence of the other two?

On the first viewing, Ali Baba deceived me; on the second bored me; on the third enraptured and delighted me. There's no doubt that I'll be seeing it again, but I well know that, having victoriously passed the perilous cape of the number 3, every film takes its place in my private, shut-up museum. (Parenthetically speaking, if every cinephile had seen Key Largo, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and The African Queen three times, there would be many less "Hustonians.")

It's not that in rewatching Ali Baba one understands or discovers more things — as happens for example with The Golden Coach, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, or Casque d'or, but following the example of musicals (Singin' in the Rain, An American in Paris, etc.) Becker's latest film succeeds in being known for being appreciated. You have to go beyond the stage of surprise, you have to be familiar with the structure of the film so that the initial feeling of imbalance has vanished. [...]

Had Ali Baba been a failure I would have defended it anyway by virtue of the politique des auteurs that my colleagues in criticism and myself practice. All based on the beautiful phrase of Giraudoux's: "There are no œuvres; there are only authors," — it consists of denying the axiom, dear to our forefathers, according to which films are like mayonnaises: those that fail or those that succeed.

From one instance to another, our forefathers came to speak, without losing any of their gravity, of the sterilizing old age, even the spoilage, of Abel Gance, Fritz Lang, Hitchcock, Hawks, Rossellini, and even Jean Renoir in his Hollywood period.

Despite its tortuous scenario by ten or twelve individuals, ten or twelve people too many with the exception of Becker, Ali Baba is the film of an author, an auteur who has achieved exceptional mastery: un auteur de films. And so the technical success of Ali Baba confirms the legitimacy of our policy, the politique des auteurs. •

===

from

Loving Fritz Lang

On The Big Heat by Fritz Lang

by François Truffaut, 1954

On the eve of writing an article that he'd like to be both general and precise, exhaustive and researched, the movie critic begins to envy of his literary confrère the privilege of the library where heavy volumes of complete bodies of work, like so much tapestry, can be consulted and quoted at will. [A telling contrast between the periods of 1954 and 2023; although my understanding is that Truffaut was an early adopter of seeing movies on videocassette in the early '80s. —CK]

It's actually rare that all a filmmaker's movies be in screening-circulation at the same time; it's the reason for which I appreciate the value of seeing the appearance, in December 1953, of a new Fritz Lang: The Big Heat, that the neighborhood theaters show Chuck-A-Luck [Rancho Notorious] and Cloak and Dagger, whereas the Parnasse rescreens Scarlet Street, and the Cinémathèque gives us one night after the next, the final German film: Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (subtitled in Danish) and the first American one: Fury (subtitled in Flemish).

Moral solitude, man conducting alone a fight against a semi-hostile, semi-indifferent universe — such is Lang's favorite theme. This theme... it's not even the titles that attest to his consistency: M [M le maudit, or M the Cursed in France. —CK], Fury, You Only Live Once, Man Hunt, etc. [...]

"The Big Heat. Neither bad, nor all that good. Fritz Lang is no longer Fritz Lang. We've known it already for a few years now. There's no more trace of symbolism in the present-day works made by the director of Metropolis. And of expressionism, still less." These few lines by Louis Chauvet are a prime example of the synthesis of sophisms that it be becomes vital to clear away. In revisiting Fritz Lang's œuvre, one is struck of what there is of the Hollywood style is his German films (Spione, Metropolis, Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse) and of what he willed to conserve from the German style in his American work (sets, certain lighting effects, a taste for perspectives, sharp angles, — in the present instance, Gloria Grahame's mask, etc.). One easily understands what might have been some irritation in the departure of the best of our European filmmakers for Hollywood, and the puerile temptation to see, in terms of exile, the clearest disappearance of their genius, — but rather isn't there chauvinism to be found in this account if our critics would prefer to adopt the opposite bias (since the grace of knowing how to watch seems to them forever refused) and declare the the best of American production comes as a result of European inspiration (Hitchcock, Lang, Preminger, Renoir, etc.)?

Another legend would have it that the American metteur en scène be a "crafty handyman" who "saves what he can" in the way of the "alarming" subjects "imposed" on him. In this case, isn't it strange that all of Fritz Lang's American films, although 'signed' by different screenwriters and shot for the benefit of the most diverse firms, very tangibly tell the same story? Doesn't this suggest that Fritz Lang might indeed be a genuine auteur of films and that if his themes, his stories, 'borrow' in order to come to us, the banal appearance of a serial thriller, a war film, or a western, one must perhaps see there the sign of the great integrity of a cinema that doesn't test the necessity of adorning itself with enticing labels? What follows is one certainty: to make something in the way of cinema, you have to pretend, or, if one prefers this slogan: to speak with the producer, disguise is de rigueur. And yet, it's true to the extent that one disguising themselves as their opposite, one won't be shocked to hear of my preference for filmmakers who imitate insignificance...

One must love Fritz Lang, salute the arrival of each of his films, to rush to them, to return to them often and impatiently await the next one (this will be, this time around, The Blue Gardenia). •

===

from

Journey to Italy by Roberto Rossellini

by François Truffaut, 1955

Here: novelty everywhere. Form, content, subject, technique, fabulism, acting, cinematography, score. Journey to Italy is the first film to take for its subject only emotion and its variations. Whence the completely musical construction of the work arranged around themes of life and of death. On one hand, in Naples, some pregnant women regard Katherine [Ingrid Bergman] with envy, and on the other hand: ashes, dust, bones. Naples is the city of miracles, the city in which — according to Roberto Rossellini — more than elsewhere there emerges the feeling of eternal life; therefore we're not surprised by a death so benevolent, smiling, and... present. Journey to Italy is the film of a state of a soul, of a difficulty in being (together) that in the end becomes, by the force of things, the dignity of purely and simply being. The Katherine of Journey to Italy is situated, morally and socially, mid-road between the sinner touched by grace, Karin, of Stromboli, and Irène of Europe '51, who attained holiness without having aspired to it. [...]

The admirable cinematography of Enzo Serafin, the score by Renzo Rossellini, take part in this novelty, this audacity. Journey to Italy might seem less uncanny that La strada; I find it more original and more audacious; sentimentality and literature having no part it in the proceedings. As with Francesco, giullaire di Dio, like Europe '51, like Jeanne au bûcher, Journey to Italy resembles nothing nothing of what's been done in cinema. Roberto Rossellini's œuvre is "outside," "on the margins"; each one of the films that compose this body of work is a total effort to liberate the screen from bygone servitude. Since Roma città aperta, Rossellini has not ceased going forward; at present he is the most personal and the newest of film-auteurs. •

===

from

On Pure Cinema

On Assassins et voleurs [Killers and Thieves] by Sacha Guitry

by François Truffaut, 1957

The term "masterpiece" is all the more hackneyed as it [still] remains to be defined. Everyone will agree with this.

Assassins et voleurs places itself under the sign of immorality. First off, immorality of a cynical scenario and a text glorifying adultery, thievery, injustice, and murder. Immorality especially of a double financial and artistic success, defying all the rules dictated by good sense and experience; paradoxical success and nearly scandalous success as we see it.

Assassins et voleurs, contrary to any of the films we defend in the Cahiers, is stripped of all aesthetic ambitio; there's not even the slightest indication of professional conscience; a boat scene, supposedly taking place on the open sea, was obviously shot on the sand — the hotel elevator doesn't rise any more than the boat moves forward, the same set being used several times; the long scene between Poiret and Serrault, divided into ten or twelve sections was obviously filmed in one afternoon with two cameras, and so crudely that by listening carefully one can hear the buses passing in front of the studio-hangar, and the technicians on the neighboring set chat happily about their work-break. [...]

This curious film, whose luck is maybe to not have been "edited" by Mary Seton, proves that success doesn't necessarily depend on misunderstandings and that a funny and insolent work without too much vulgarity, interpreted by worthy actors who are not stars and who direct themselves, filmed without a metteur en scène, a work thrifty to the point of destitution, sloppy to the point of provocation, is welcome in a production that gets bogged down by shyness, cowardice, delusions of grandeur, snobbism, and systematic distrust. •

===

All Alone

by Jean-Luc Godard, 1984

...A film is something that goes... from one's self... comes and goes... from one's self... when he wrote... threw his writing... outside himself... against a certain tendency of the French cinema... François reproached them for not having gone from themselves... to make cinema... an entire cinema... before making films... to leave their home... like the true spectator... every admission into a theater is an exit of the spectator from their own home...

...François started out making cinema with his hand... ink stains... paving-stones in the sea... he didn't hesitate to cast upon others his first stone... I don't know if he continued... one can't do everything... to take on the sins of others before one's own... he did everything everything all alone... everything giving the opposite appearance... so he's dead from it... a film is never made alone... in solitude... yes... often... the white page and the white screen... everyone knows it as such [c'est connu comme le loup blanc]... but wolves [les loups] precisely... or the killers of which Henri Langlois speaks... who smile at you...

...We knew that a film was made alone... but we were four... so it took us a long time to admit it to one another... then certain ones recanted... the screen was our examining magistrate...

...There was Diderot... Baudelaire... Élie Faure... Malraux... then François... there was never another art critic... François was French... he's dead from it... the cinema being international first of all... he smuggled it out of his skin [de sa peau]... on the sly [en douce]... without Uncle Jean [Cocteau] around to help him traverse the mirror... his only passport, books... do you want some books, well here they are... too much information... it goes to the brain... one goes to see Father Alfred so he clears your name... again, a book... the two remained forbidden, speechless [interdits]... etymologically between the real and the imaginary... we will certainly meet them again... •

===